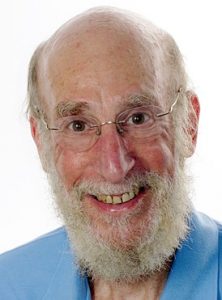

Stanley Tweyman is University Professor of Humanities and Graduate Philosophy at York University, Canada. We invited him to answer the question “What norms or values define excellent philosophy of religion?” as part of our “Philosophers of Religion on Philosophy of Religion” series.

Stanley Tweyman is University Professor of Humanities and Graduate Philosophy at York University, Canada. We invited him to answer the question “What norms or values define excellent philosophy of religion?” as part of our “Philosophers of Religion on Philosophy of Religion” series.

Hume’s Excellence regarding the Cosmological – Ontological Proof of God’s Existence.

In this blog, I propose to examine one of David Hume’s criticisms of the Cosmological – Ontological proof of God’s existence, a criticism which I will show is decisive against this argument.

First, the argument. Any object that currently exists is related causally to a chain or succession of objects which extends back to infinity. Demea (the one who presents this argument) argues that, although particular members in the chain or succession can be accounted for by reference to earlier members in the chain, nevertheless, two questions remain unanswered: “Why is there something rather than nothing?”, and “Why does this particular succession of causes exist rather than some other, or no succession at all?” Demea contends that these are legitimate causal questions, which can only be answered by making a modal leap. Since no contingent being can account for the eternal (backward) chain of causes and effects (any such contingent being would be a member of the succession and, therefore, part of the problem), and since we cannot explain the chain through either Chance (chance for Hume means no cause, and Demea regards this as meaningless, and, therefore, unintelligible) or Nothing (ex nihilo nihil fuit), Demea concludes that we can explain the infinite or eternal succession only by having recourse to “a necessarily existent Being, who carries the REASON of his existence in himself; and who cannot be supposed not to exist without an express contradiction” (D. 149). According to Demea, therefore, the eternally contingent must be grounded in the eternally necessary.

I now turn to the criticism of this argument, which I regard as decisive:

“Add to this, that in tracing an eternal success of objects, it seems absurd to enquire for a general cause or first author. How can any thing, that exists from eternity, have a cause, since that relation implies a priority in time and a beginning of existence?” (D.150).

As everyone knows, Hume is adamant that we never understand the powers of objects through which they act as causes of certain effects. Hume is equally adamant that designating an object as a cause, and another as effect, requires seeing objects of those types constantly conjoined. In one respect, constant conjunction assists us by generating the habit or determination of the mind, so that we naturally associate the cause with the effect (this, in the language of the Treatise, is causality as a ‘natural relation’). In so far as causality is viewed as a ‘philosophical relation’ (once again, utilizing the language of the Treatise), the importance of constant conjunction is this: even though we lack any insight into causal power, the constant conjunction between objects convinces us of the causal relevancy of one object to another. The powers of the first object, although unknown, appear to be directed to the production of, or a change in, the second object.

Applying this analysis of the importance of constant conjunction to ascriptions of causality to our discussion, we can understand the full weight of Cleanthes’/ Hume’s criticism in the eighth paragraph of Part 9. The most useful way of developing what I have to say here is to revisit Demea’s argument, at the point at which he seeks to answer the questions: why is there something rather than nothing; and why does this particular succession of causes exist from all eternity rather than some other, or no succession at all? As we have seen in the second paragraph above, Demea offers four possible explanations. The elimination of the first three, he urges, leaves us with the fourth: the only reasonable explanation as to why there is something rather than nothing, and why there is what there is rather than something else, is that a necessarily existent being exists, who is the cause of the world, as we know it.

But this is where Demea errs, given Cleanthes’ criticism in paragraph 8 of Part 9. Given the Cleanthean/ Humean account of causality, establishing a necessarily existent being as the cause of the eternal chain of causes and effects would require the observation of constant conjunction between this being and the causal chain – this is required in order to establish the causal relevancy of the existence of the one to the production and existence of the other. Since this requirement cannot be satisfied, Cleanthes is arguing that we cannot establish that a necessarily existent being is the cause of the eternal chain of causes and effects, even if the chain and its members are contingent, and even if we have eliminated the other three putative causes.

We can develop Cleanthes’ criticism even further. Assume for the moment that we already know (i.e. independently of Demea’s argument) that a necessary being exists, and that the eternal chain of causes is contingent. Following Cleanthes’ criticism in paragraph 8, which focuses on the role of constant conjunction, it would still be impossible for us, using Demea’s premises, to show that one is causally relevant or responsible for the other. Each would exist in a manner which appears to be incompatible with its having been caused. What exists in what we call the world might someday cease to exist, and in this respect, we might be tempted to say that what exists exists contingently. But even if this is true, Cleanthes/ Hume has established that the eternity of the world, at least in terms of its not having had a beginning, prevents us from proving that it was caused to exist. Accordingly, it may be the case that the eternal causal chain of which Demea speaks is contingent and uncaused, or at least from an epistemological point of view, must be so regarded.

Hume holds that his first argument against the Cosmological – Ontological Argument (concerning the non – demonstrability of existential statements) is “entirely decisive”, and he is “willing to rest the entire controversy upon it” (D.149). My point in this blog is that Hume understates the force of subsequent criticisms of this argument, inasmuch as at least one of these additional criticisms is decisive.