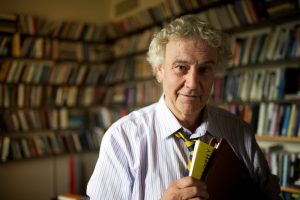

Eric Charles Steinhart is Professor of Philosophy at William Paterson University. He has degrees in computer science and in philosophy. He has authored Your Digital Afterlives, Believing in Dawkins, and Atheistic Platonism. We invited him to discuss comparative philosophy of religion as part of our “Philosophers of Religion on Philosophy of Religion” series.

Eric Charles Steinhart is Professor of Philosophy at William Paterson University. He has degrees in computer science and in philosophy. He has authored Your Digital Afterlives, Believing in Dawkins, and Atheistic Platonism. We invited him to discuss comparative philosophy of religion as part of our “Philosophers of Religion on Philosophy of Religion” series.

By now I suppose pretty much everybody has heard the critical thesis that traditional comparative philosophy of religion (CPoR) has a rather dark past. It was a colonial project. Or even that the very category of religion (especially “world religions”) was invented by missionaries in the British Empire. It’s increasingly recognized that the history of CPoR has been extremely Christo-normative, and often very destructive for non-Christians. Still, if it can change its ways, I think CPoR can have a brighter future.

The old way of doing CPoR appears in slogans: religion is like an elephant; all religions are different paths up the same mountain. A bit more deeply: all religions share a common mystical core; God has many faces; God has many names. One elephant, one mountain, one mystical core, one God. More philosophically, CPoR produced John Hick’s pluralism, in which all religions are different human ways of experiencing and responding to “the Real”. One Real, not many Reals. God becomes more abstract, so that religions are about “the ultimate”, “the holy”, “the divine”, “the transcendent”. Always the definite article “the”, and never plural. Always one, never many.

Even more parochially, traditional CPoR accepts the Protestant axiom that religion is mainly a matter of propositional content. It’s not hard to find illustrations of the view that religions are all different “faiths” or about “beliefs”. On this view, a religion amounts to a kind of ultimate theory, which is more or less true of ultimate reality. And there is only one ultimate reality, that is, one possible world, so religions more or less correctly describe this one world. Religions obviously make incompatible truth-claims: God has a son; God has no son. For the pluralist, the favorite strategy has been to see these as different aspects or parts of the One Ultimate Reality (see “the elephant” or “the mountain”). For the pluralist, every religion gets some but not all of “the truth” about “the ultimate” or “the transcendent”. Always with the definite article, and never plural.

Yet the alternative seems to be an incoherent cultural relativism: all religions are equally true! Why is this incoherent? Because religions really do make truth-claims, and they really do conflict. The pagan says there are many gods; the monotheist that there is one god; the atheist that there are no gods. These conflicts cannot be reconciled by finding some occult unity. They are incompatible. One popular way out of these troubles just says that religions are linked by family-resemblance. Unfortunately, the family-resemblance view is true because it is trivial. Everything resembles everything else.

I think the most positive way forward for CPoR requires rejecting its central Protestant axiom. Religions are not efforts to find the one true theory of the one ultimate reality. Religions don’t have anything to do with ultimate reality (or realities), because the ultimates are studied by entirely secular logic, mathematics, and metaphysics. Far from being descriptive, religions are ways of actively relating to other possible worlds. Here I recommend the modal realism of David Lewis: there are many possible worlds, they do not overlap, and no thing is in more than one possible world. Each religion makes truth-claims about its own world, which is not the actual world, and it makes truth-claims about no other worlds besides its own. Religions are incommensurable. Different religions are comparable, for example, in the number of gods in their respective worlds. But this comparison reveals difference rather than unity. There are many transcendent ideals, many stars, many mountains, many orderings of sacred values.

If actively relating to another possible world is a kind of climbing, then every religion climbs its own mountain. Does this mean religions deal with ethics? It does not. Ethics, too, is the province of entirely secular logic and philosophy. Our common morality emerges logically, naturally, and rationally from objective and necessary facts about persons. Religions are neither descriptive theories of ultimate reality, nor ethical theories of how humans ought to treat each other. Nevertheless, there are many non-ethical questions about how humans ought to live. But even these belong to the entirely secular study of human flourishing. And here CPoR has many questions to address: how do different religions treat women? Do they treat women justly or unjustly? CPoR can use objective, secular norms to ethically evaluate religions (and gods). In what ways are religions good? In what ways are they evil?

What is left for religion? As ways of engaging other possible worlds, religions deal with ideals that are not primarily ethical, but which enter ethics in foundational ways. Is it ethical to for mountaineers to free-solo? This depends, in part, on your assessment of the non-ethical value of free-soloing. If you think free-soloing is a way for humans to participate in superhuman or transcendental ideals, your answer will be yes. Otherwise, no. Different religions reveal different ideals. There are transcendental values, values which exceed all utilitarian computations, but these are incommensurable, and they are fully realized only in diverse possible worlds. Because there are many worlds, these values do not conflict. This is pragmatic value-pluralism. These transcendental values resemble aesthetic values, ways in which human conduct gains superhuman beauty. Religions are genres of pragmatic-aesthetic practices. They are different aesthetic ways of life, different ways of pursuing styles of aesthetic excellence beyond the human.