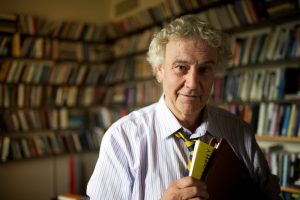

Charles Taliaferro is Professor of Philosophy and Overby Distinguished Chair at St. Olaf College. He is the author or co-author of over 30 books, including the two editions of the Blackwell Companion to Philosophy of Religion. He is the author of the Philosophy of Religion entry in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy and Editor-in-Chief of Open Theology. We invited him to answer the question “Is there a future for the philosophy of religion?” as part of our “Philosophers of Religion on Philosophy of Religion” series.

Charles Taliaferro is Professor of Philosophy and Overby Distinguished Chair at St. Olaf College. He is the author or co-author of over 30 books, including the two editions of the Blackwell Companion to Philosophy of Religion. He is the author of the Philosophy of Religion entry in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy and Editor-in-Chief of Open Theology. We invited him to answer the question “Is there a future for the philosophy of religion?” as part of our “Philosophers of Religion on Philosophy of Religion” series.

In my 40 years in higher education and in giving invited lectures in philosophy of religion at major universities in the USA and UK (Harvard, Yale, U of Chicago, Oxford, Cambridge…) and elsewhere (Russia, China, Brazil) I have found eager audiences hungry for philosophy of religion. Given the overwhelmingly large population of religiously identified persons on this planet (PEW estimates 84%) for philosophers to ignore the importance of religious belief and practice would be negligent. While some popular news media report a decline in religion in parts of the world, sociologists of religion like Randy Stark (in his book The Triumph of Faith; Why The World is More Religious Than Ever) contend that low numbers are often generated if ‘religion’ is defined in terms of membership in churches, temples, and so on; but if ‘religion’ is measured in terms of frequency of praying, believing there is a God or Higher Power, visiting shrines, and so on, numbers are extraordinarily high. I have also seen a study where it was assumed that if persons are self-described atheists then they are classified as non-religious (see chapter one of Stark’s book). But Buddhism is widely considered a religion and it is atheistic. The most well recognized and perhaps best loved religious leader today, the Dalia Lama, is an atheist (or, if you prefer a more modest term ‘a non-theist’; either way, he is quite explicit in denying the reality of a Creator-God).

I suggest that of all the sub-fields of philosophy, philosophy of religion is hard to surpass in terms of addressing what people actually care about. Perhaps the sub-fields of ethics and political philosophy have a stronger claim in terms of maximum relevance to all peoples, but keep in mind that both ethics and political philosophy raise concerns that are religiously significant and are treated in the philosophy of religion literature (e.g. the Euthyphro dilemma, the status of religious claims in a pluralistic, liberal democracy).

Two recent developments in philosophy of religion that are exciting involve its interdisciplinary nature and its transcending a divide between analytical and continental modes of inquiry.

On the interdisciplinary side, one has only to look at the massive attention given to the relationship between science and religion. We have come a long way from the distorted conflict model of Draper and White. To be sure there are philosophers like Daniel Dennett who charge that contemporary science undermines a host of religious claims. But there are just as many, if not more, philosophers who deny the significance of this, such as Michael Ruse, himself a secular atheist, who distinguishes science casting doubt on Biblical narratives of Eden and the Flood from addressing cosmic questions about the meaning of life. The ways in which philosophy of religion can interact with other disciplines investigating religion is evident in the 2021 The Wiley Blackwell Companion to the Study of Religion, second edition, edited by Robert Segal and Nickolas Roubekas.

On overcoming the analytic versus continental divide, a more inclusive (less partisan) method of practicing philosophy of religion is apparent among philosophers who draw on aesthetics and the philosophy of art: Mark Wynn, Victoria Harrison, Gwen Griffith-Dickson, Douglas Hedley, David Brown, Anthony O’Hear, and others. In my own work, I have sought to be neither narrowly analytic nor narrowly continental but to draw on sources in both, as in the book I recently co-authored with the American painter, Jil Evans, Is God Invisible? An Essay on Religion and Aesthetics (CUP 2021).

A further sign of the exciting vibrancy of the field will be published this summer: the four volume Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Philosophy of Religion with over 470 entries by over 350 scholars (mostly philosophers, and some historians of ideas and culture) from around the world; I am the senior co-editor with Stewart Goetz with five associate editors and fifteen assistant editors. Contributors include philosophers who practice the religious traditions they address as well as multiple secular philosophers. Readers of this blog may know that Stewart and I are philosophers who are practicing Christians, but the different editors and contributors include huge numbers (the vast majority) of non-Christians and some who are quite critical of Christian philosophy (e.g. John Schellenberg). One of the main associate editors, the outstanding philosopher of religion, Graham Oppy, is not hostile to theism or Christianity in particular, but, as a well-known advocate of non-theistic positions (atheism / agnosticism), he has insured that non-theistic arguments are in no short-supply in the Encyclopedia.

What of the complaint that philosophy of religion today is too Christian in its orientation or too stagnant and not showing signs of progress (or development) such as we see in the sciences?

On Christianity: I have, of course, indicated that the forthcoming Encyclopedia offers widespread resources for philosophers to engage in non-Christian traditions. This is most thorough in terms of religions in India, China, Nepal, Korea, Japan, and Southeast Asia, but attention is also given to South America and African traditional religion (an area addressed in Is God Invisible?). A contemporary philosopher of religion, Thaddeus Metz (University of Pretoria), is engaged in excellent philosophical treatments of traditional African religions and ethics. Chad Meister and I edit a series with Routledge on contemporary philosophical investigations into religion. So far, the published volumes are on Hinduism, Buddhism, Daoism, Judaism, Islam, and even on religious naturalism (the later by Graham Oppy). Christianity is next on the list, but we ensured first that non-Christian religions were engaged. Having taken note of the welcome expansion of philosophy of religion, it should also be noted that Christianity and Islam are the two largest religions today in terms of numbers (e.g. in terms of Africa, it is estimated that 40% of Africa is Christian and 40% Islamic); it is not odd that philosophers who want to engage large numbers of persons on this planet would prioritize their attention on Abrahamic traditions. Moreover, there is a growing appreciation of philosophical debates in Ancient and Classical Indian philosophy over monotheism and natural theology (arguments from the structure of the cosmos to Brahman, anti-theistic arguments from evil) that are of course relevant to the Abrahamic faiths but developed independent of those faiths. See, for example, God and the World’s Arrangement: Readings from Vedanta and Nyay (Hackett).

As for whether contemporary philosophy of religion seems stagnant to some critics, I suggest that some of these complaints come from philosophers whose arguments on various topics (e.g., contending that classical theism is incoherent or ridiculously improbable) have not been universally accepted by other philosophers of religion. Some of these critics go so far as to accuse their unpersuaded colleagues of not being truly philosophers, but apologists. I will not charge them with arrogance (for all I know, these critics are humble and believe they are open-minded), but I do suggest that they overestimate the power of their own arguments / positions, and fail to appreciate some lessons from history. From time to time, philosophers have proclaimed that this or that position is the only game in town. Not long ago, the later Wittgenstein’s work was deemed unassailable, Marxism once achieved virtual consensus, logical positivism did the same, and today there are some philosophy and religious studies departments that seem to rule out anything other than naturalism. I suggest that the current orthodoxy stands as much promise of being an enduring monolithic stance as former orthodoxies. I have been in graduate seminars at Harvard in the 1970s when anything other than nominalism was considered a joke, while only a little later and less that 100 miles away at Brown University, Platonism was all the rage. At Oxford and Cambridge up through the 1980s Wittgenstein’s private language argument was considered to be invincible, only to become a minority position in the 1990s. Bertrand Russell concluded his famous history of philosophy declaring the ontological theistic argument dead. Those keeping up with the literature know this has turned out to be false. There is a saying that old soldiers never die, they simply fade away; it has also been remarked that philosophical debates (such as theism versus naturalism) are different from old soldiers—not only do they not die, they never fade away. I believe there can be (and has been) progress in philosophy. The most recent version of the ontological argument in print is better than Anselm’s. But reaching consensus on the titanic views in metaphysics, epistemology, and value theory inside and outside philosophy of religion is as elusive as ever.

To sum up: My experience in the classroom and in multiple contexts culturally from Brazil to New York City, China, and so on, indicates to me the vibrancy of philosophy of religion. The field has been a vital site for me to bring the resources of philosophy to bear in support of the Black Lives Matter Movement. I have given pro-BLM lectures in the UK, the USA, and in my college, as well as addressing systemic racism in four books. Philosophy of religion is the highest over-enrolled course in my college with waiting lists of 50 or more students. I suggest that a philosophical education (undergraduate or graduate) without philosophy of religion, would be Hamlet without Gertrude, Hamlet, Ophelia, and the rest of the crew.