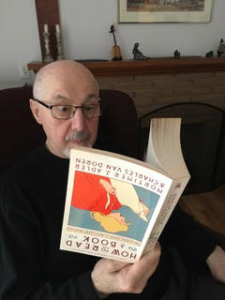

Gary Colwell is Professor Emeritus of Philosophy at Condordia University of Edmonton. We invited him to answer the question “What is Philosophy of Religion?” as part of our “Philosophers of Religion on Philosophy of Religion” series.

What is Philosophy of Religion? An Almost Serious Approach

The title “Philosophy of Religion” has three words which, when examined closely, will reveal the meaning of the discipline to which the whole title refers. (Or perhaps not, as the case may be.) Let us first inspect the word “philosophy” and then the word “religion”. In the end we shall see that the little word “of” holds the key to the most useful definition of the title; for whatever “philosophy” and “religion” mean, we know right off that the title refers to a philosophy that belongs to, or is applied to, religion.

What is philosophy? Philosophy is a rational discipline from which we learn more and more about less and less until someday we know everything about nothing. Or going the other way, we learn less and less about more and more until someday we know nothing about everything. The crucial question arising from these two definitions is itself philosophical in nature. Which should you rather know: everything about nothing or nothing about everything? For the benefit of the conscientious reader there is a right answer to that question.

I faintly hear someone saying, “get serious!” OK, I will, but you won’t like it. What I’m going to offer you is a functional and compendious definition of philosophy that is not entirely serviceable. But a word of caution before you proceed. You mustn’t say this definition out loud for fear of frightening your dog or alienating your other friends, though interjecting it skilfully into a cocktail conversation among the literati will garner you a heap of praise. Here goes: Philosophy is a rational discipline in which careful attention to detail, logical thinking and imagination are used to question, describe, analyse and speculate upon the fundamental assumptions of our beliefs about reality or some limited aspect of it, while striving to be clear, truthful, consistent and reasonable in its spoken, unspoken and written accounts. Admittedly, that was a bit long. But how to shorten it without amputating some of its vital limbs – that is a vexing question. We do need to retain the ideas of both analytic and synthetic thinking, with the understanding that when we engage in such thinking we are asking questions as well as making statements. Perhaps we could employ the term synalytic thinking. On second thought, that would only complicate the issue and raise unnecessary additional questions. Let us, then, tentatively settle upon the following: philosophy is a rational discipline in which analytic and synthetic thinking are trained upon the fundamental assumptions of some aspect of the world, in this case, religion. But now we must ask, what in the world is a religion?

Defining “religion” is like trying to wallpaper an alligator. On the one hand it is tempting to say simply that a religion is a system of beliefs with god at its apex. But this would make the definition too narrow. It would eliminate Theravada Buddhism, the non-dualistic schools of Hinduism such as Advaita Vedanta, and various kinds of polytheism. Many systems of belief that are labelled “religion” do not posit the existence of one transcendent being that is thought to be worthy of worship. On the other hand one might modify one of Tillich’s ideas and say that religion is simply a belief system that organizes life around that which ultimately concerns some group of people. This, however, would include practically everything upon which we may set our highest interest and around which we can organize our lives, making the definition too broad.

Why, we may rightly ask, are all these different systems of belief called “a religion”? It’s as though a giant strode about the earth collecting one after another of these belief systems in a huge basket: B was included because it was somewhat like A; C was included because it was somewhat like B; D was included because it was somewhat like C; and so on to n-1 and n. But when the giant was done he looked in his basket and discovered that n had almost nothing in common with A. Unwittingly he had gathered his religions according to a “family resemblance” method of collection. But why did he collect A in the first place? I don’t know. Maybe it seemed like a good idea at the time. Or perhaps it was because the first system of belief he came across was focused upon a transcendent source that provided meaning for his life. Whatever the reason, his first and last collections had much less in common than his first and second collections.

Is there anything we can do to build a definition of religion that is both accurate and serviceable? One approach might be to “bite the bullet”; in other words, to go for the generality and live with the consequences. We could say that a religion is a life-guiding system of belief that often but not always has a transcendent being at its apex. We do catch communism with such a wide net, but then calling that particular belief system a religion is hardly a new idea, though admittedly communists have never liked it very much.

To avoid alienating some of our ideological colleagues, therefore, we could use the opposite approach by defining “religion” specifically, even ostensively. It is that religion, X, that I mean when I say “philosophy of religion”. And we can substitute for X any religion that holds our interest. But now rather than trying to define the “philosophy of religion” simpliciter, we will need to adjust the explanandum to read, for example, “the philosophy of Christianity”. It could as well be “the philosophy of Islam”.

Still, something doesn’t feel quite right about my attempt to define “Philosophy of Religion”. I seem to have knotted my thinking into a mental cramp. I have accomplished this by trying to make my definition of philosophy of religion at one and the same time general and specific, as well as concise and expansive; and I also want it to be portable, so to speak. What to do? The thought now occurs to me that there is no need to satisfy all these characteristics at one stroke. For where is it written that we must say everything about something at once? So let’s make another run at the definition and do it in stages. I’ll call this effort an engaging definition, for it is supposed to engage the reader or hearer to ask successively more specific questions about previously more general answers. It will involve a dialogue that goes something like this:

Q – What is Philosophy of Religion?

A – It is a rational discipline in which philosophical thinking is applied to a religion.

The results may be spoken, unspoken or written.

Q – Why do you say rational discipline?

A – Well, because reason and the imagination are used exclusively to practice it.

There are many kinds of discipline or areas of accomplishment that invite mastery; not all of them are exclusively or predominantly rational. Taekwando is one example.

Q – But that still doesn’t explain what philosophical thinking is.

A – True, but just ask me and I’ll be glad to explain.

Q – All right, what is it?

A – I thought you’d never ask. It is the kind of thinking that strives to be clear, truthful, logical and consistent in its spoken, unspoken and written accounts. It is typically argumentative, seeking to create sound arguments for certain ideational positions, arguments with true premises and valid conclusions.

Q – But aren’t these just the features you should expect to find in the conscientiously practiced disciplines of chemistry, psychology or art history?

A – Yes, but with this very important difference: philosophical thinking is trained upon foundational assumptions. Philosophers work in the basements of other disciplines. You know, where it’s dark and the mushrooms grow.

Q – Do you mean to say that philosophical thinking never leads anyone to build superstructures? They never construct anything above the basements?

A – Goodness, No! Much of philosophy has been and continues to be speculative. Indeed, there have been some grand systems of thought built during the history of philosophy. Yet their construction was begun only after their builders had created or uncovered those foundational assumptions upon which they thought their systems could be solidly built. And the destruction of these same systems was brought about at the same fundamental level when deep cracks were discovered in the ideational foundations.

Q – You said that philosophical thinking is applied to a religion. What religion are you referring to?

A – Pick any one you like. Take Christianity, for example. Some of its foundational assumptions are: God exists; God is triune; God created the world; God is love; Jesus is divine; Jesus rose from the dead; miracles occur or have occurred; there is an afterlife; and so on. These are some of the assumptions without which the religion called Christianity wouldn’t be what it is. When philosophical thinking is trained upon these foundational assumptions those who are engaged in such thinking are doing philosophy of the Christian religion.

Q – Surely a definition of “religion” ought to include more than one religion.

A – Actually it does, at least at first approximation. But it includes all of them only indefinitely, using the article “a” in the phrase “philosophical thinking applied to a religion”. If you want greater specificity then simply ask, as you did earlier, “what religion are you referring to”, and I shall answer just as I did before, “pick any one you like”. I could just as well have referred to Judaism or Islam, and we could just as easily have trained our philosophical thinking upon the foundational assumptions of either of them.

Q – You said that one of the foundational assumptions of Christianity is that God exists. Don’t all the Abrahamic religions have this as one of their assumptions? As the most important of all their common assumptions, doesn’t it unite all of them? They all believe in a supreme being, don’t they?

A – Yes they do, but here’s the catch. The devil is in the details…Let me rephrase that. The specific natures of the supreme beings in whom they believe are radically different from one another.

Q – How could that be? What can be more than supreme?

A – It is not the degree of greatness that is at issue but rather the degree of generality and vagueness. Let me ask you a question: what do a chair, a lamp and a coffee table have in common?

Q – Well, they have many things in common. For one, they are all solid objects. As well, they are all artefacts. Most obviously, I guess, they are all pieces of furniture.

A – Good. Now, what if I told you that a chair, a lamp and a coffee table are basically the same kind of object because they share in common the property of being a piece of furniture.

Q – I’d say you were daffy.

A – Why would you say that?

Q – Because the word “furniture” is just a collecting term, one that categorizes and holds together a number of objects or even types of objects found in buildings of various kinds. It’s just a shorthand way of speaking of a number of things in a spatial collection. There isn’t something in addition to the three objects you named that we can refer to and identify as furniture. The word isn’t even a quality term like “red”.

A – Precisely! And it’s for the same reason that we cannot say that the three Abrahamic religions worship basically the same god because their gods share in common the property of being a supreme being. Just as a chair, a lamp and a coffee table are radically different pieces of furniture so the gods of Judaism, Christianity and Islam are radically different gods, even though all three gods are supreme beings in the minds of their respective devotees. You might observe that a coffee table is more similar to a chair than it is to a lamp but this greater similarity would not diminish one bit the radical differences that exist between all of them. Nor does the observation that the triune god of Christianity is more similar to the god of Judaism than he is to the god of Islam remove the profound and ineradicable differences that exist between all of them. And it’s the profound differences, Q, that prevent us from finding a definition of “religion” that one and the same time is both general and substantive. We can of course build a compendious definition of “religion”, just as we can of “philosophy”, but we lose in utility what we gain in substance. We end up with a long grocery list sprinkled with qualifications.

Q – Why then do so many intelligent people think that these religions worship basically the same god?

A – Because at a high enough level of abstraction any two things can be made to seem the same. What do a pickle and a paper clip have in common?

Q – They have many things in common. They are both visible substances; they are both oval shaped; their names both start with “p”.

A – Well done, Q! And you could also have added that neither of them can ride a bicycle. Or to put it more positively, they are both bicycularly challenged.

Q – That’s a very wispy similarity.

A – Yes, and so are the ones you mentioned, even if not quite so wispy. Saying that the two objects are “substances”, “oval shaped” and “have names beginning with ‘p’” tells me little about the essential nature of the objects you seek to compare.

Q – However that may be, the three monotheistic religions I mentioned have substantially more in common than a pickle and a paper clip have. All three religions have canonical scriptures, a revered prophet or prophets, a system of ethical teaching, a way of salvation, and so forth. There are many substantive similarities.

A – I’m afraid that I can’t entirely agree, Q. The wispiness index is still very high in the alleged similarities you mention. Certainly there is much substantive overlap between the scriptures of Judaism and Christianity. Even so, the Hebrew Bible composes only about seventy-five percent of the Christian Bible. And the twenty-five percent difference, found in the New Testament, throws a new light on the whole. The Koran, being approximately the size of the New Testament, is radically different in content from both of them. Furthermore, if you look in detail at lives of the preeminent prophets of Islam and Christianity you will again see profound differences between them. And the same holds for their respective ways of salvation.

Q – But you’re emphasizing the differences and not saying much at all about the similarities.

P – That’s deliberate. And it’s because we are talking about the definition of “religion” in the title “Philosophy of Religion”. And I’m trying to point out the futility of attempting to form a general definition of “religion” that is both accurate and substantive. It’s the profound differences between the foundational elements of the religions that give those religions their distinctive character, and it’s these differences that frustrate any effort to form an inclusive definition that is both accurate and substantive. It is better not to try to include the foundational elements of all religions in the initial stage of an engaging definition, for it widens the field too much, causing one to make vague and implicitly untrue claims. Better, I think, to send the enquirer to a religion where first s/he can uncover its foundational assumptions and then apply philosophical thinking to them. After doing this with a number of religions there will no doubt be legitimate comparisons that can be made. But once again, it’s better not to attempt the comparisons at the initial stage of the engaging definition.

Q – If your approach is correct for defining “philosophy of religion”, why couldn’t it be used to define other sub-disciplines of philosophy? Words like “science” and “art” cause no end of definitional problems. Instead of thrashing about looking for the quintessential substance of all sciences, why not just define “philosophy of science” as “philosophical thinking applied to a science”, say, physics? You could then limit the scope of your investigation to “philosophical thinking applied to physics”. And you could do the same for art: philosophical thinking applied – not to art in general – but to an art, say, music; again limiting your investigation to “philosophical thinking applied to music”.

A – Very perceptive of you, Q! But our time is running out; we shall have to leave off discussing that until we meet again.

Q – Thank you, O sage of the northern prairie, for demuddifying my understanding.

A – Please, do not make fun of me. This is nearly serious business.

Conclusion: If you are asked what Philosophy of Religion is, don’t try to say everything at once. If you do you will find yourself either composing a very long definition that may be accurate but won’t be serviceable, or, settling for a shorter version that will quickly invite counter-examples. Begin instead with a short and grammatically correct definition that properly relates the two main ideas whose contents at first you keep indefinite. Then, with questions and answers, define the contents. You can begin by saying that it is a rational discipline in which philosophical thinking is applied to a religion. You can even leave off the first part, “a rational discipline in which”, if the context is agreeable to doing so. The short of it is this: “philosophical thinking applied to a religion”. If you have a penchant for parsimony you can shorten even further to “philosophical thinking about a religion”. You can then begin to fill it with accurate content by asking your audience, “What further questions do you have?”

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: Thank you Steven Muir and Travis Dumsday for your helpful comments on the penultimate draft.