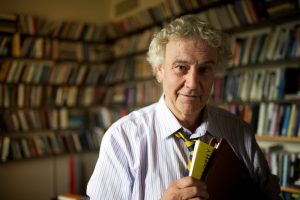

N. N. Trakakis teaches Philosophy at Australian Catholic University and writes and translates poetry. We invited him to answer the question “Is there a future for the philosophy of religion?” as part of our “Philosophers of Religion on Philosophy of Religion” series.

N. N. Trakakis teaches Philosophy at Australian Catholic University and writes and translates poetry. We invited him to answer the question “Is there a future for the philosophy of religion?” as part of our “Philosophers of Religion on Philosophy of Religion” series.

In his film, State Funeral (2019), director Sergei Loznitsa has assembled fascinating, and until now unseen, archival footage of the funeral staged for Joseph Stalin after the dictator’s death on March 5, 1953. We see Stalin lying in state in Moscow’s House of Trade Unions (the very site of the 1930s show trials), before being transported to the mausoleum in Red Square to lie beside Lenin’s embalmed corpse. One of the extraordinary features of the film is its beautifully stark and solemn, but perhaps also unintentionally subversive, portraits of the multitudes of ordinary people, officers and dignitaries that had descended upon the capital in the freezing cold to pay their last respects to the Great Leader, some in hysterics and tears (of sorrow? or secret satisfaction?), but most with blank faces, unwilling to show their hand, as they had learned so well to do.

Loznitsa provides no contextualising commentary (except for the closing credits where Stalin’s crimes are adumbrated). Instead, the viewer is compelled to make sense of what is happening, not as a detached observer but as a Muscovite immersed in the mourning throng. The director’s gambit is that one will emerge, not nostalgically glorying in the past (as the footage originally intended), but stupefied and despondent (which is how many critics have reportedly felt). This sense of disillusion and disorientation arises from the dark truths that the images reveal, subtly aided by the director’s editorial hand. Continue reading