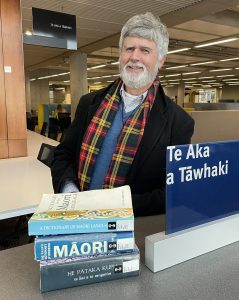

Fritz Detwiler is a retired professor who taught philosophy and religion for the last 39 years at Adrian College in Michigan. His specialty is Native American philosophy with a subspecialty in Tlingit, Navajo, and Lakota lifeways and worldviews. You can contact him at fdetwiler@adrian.edu. We invited him to discuss comparative philosophy of religion as part of our “Philosophers of Religion on Philosophy of Religion” series.

Fritz Detwiler is a retired professor who taught philosophy and religion for the last 39 years at Adrian College in Michigan. His specialty is Native American philosophy with a subspecialty in Tlingit, Navajo, and Lakota lifeways and worldviews. You can contact him at fdetwiler@adrian.edu. We invited him to discuss comparative philosophy of religion as part of our “Philosophers of Religion on Philosophy of Religion” series.

Unified Knowledge

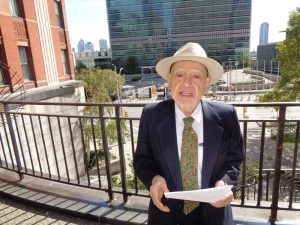

Vine Deloria, Jr., one of the most highly respected Native philosophers and critics of Western metaphysics, spent his life’s work pursuing commonality between Native and Western philosophy. His goal was “understanding the unifying reality underlying all existence”.1 His critique of the West was their belief in the superiority of Western thought and their unwillingness to take alternative perspectives seriously.

Following Deloria’s lead, the purpose of this essay is not to critique Western philosophy but to open Western philosophers to alternative worldviews to enrich their own perspectives. Following Western ways of thinking, the article divides Indigenous thought into categories familiar to Western thought. The goal, however, is to show how all these pieces fit together in a unified whole.

In the following essay, I use “Indigenous” as a blanket term for Native Americans and the First Nations people of Canada. While much of what follows extends to Indigenous peoples beyond North America, I will let others with more expertise in those areas draw their conclusions. The unified knowledge to which the title refers does not mean that all Indigenous peoples have the same conceptions of the universe. The opposite is more accurate. Indigenous peoples honor multiple viewpoints even within their communities. The argument here is that they share many of the conceptualizations developed below. Unified knowledge here refers to how all aspects of their worldviews flow into each other in contrast to many Western approaches that segment knowledge into various domains.2

Indigenous Worldviews

Metaphysics: The most distinguishing aspect of Indigenous metaphysics is “life force.”3 Life force is a power that wills the well-being of all types of persons and aims for harmony among beings. Like a woven tapestry, life force animates everything and flows through and connects everything. While present in all beings, life force is unique to every type of being and every member of different classes. Bears have bear life force, corn has corn force, and individual bears or corn plants have their unique life force. Some bears are stronger than others, for example. The uniqueness of bears or corn plants arises from their particular interactions with other life forces; just as two people may share a dog, a dog’s life force flows to and through us differently. Separate nations call life force by various names: manitou (Ojibwa), orenda (Haudenosaunee), takuskanskan (Lakota), niłch’i (Navajo), among others.

Cosmology: Indigenous cosmologies are relational and moral.4 Every being through whom life force flows connects to everything else with a dynamic and fluid intersubjective cosmos.5 The intersubjective cosmos is based on “the responsible actions of creative living beings acting collectively.”6 The moral force of the cosmos is discussed below. Relationality acts in two ways to connect beings with each other. First, all beings derive from a single source, and second, as mentioned above, life force flows through everything and interpenetrates the other beings by directly interacting with them. The cosmos is in a constant process of relationality where beings continuously exchange life force, and relationships are continually changing and reconstituting.

Ontology: The cosmological scope of the above claim becomes more evident through Indigenous ontologies. To this point, I have used the term “beings.” The better ontological term is “persons.” The category extends to all phenomena who are animate or potentially animate. All persons are sentient, active, volitional, have interests, and act intentionally.7 In a relational world, potentiality becomes actuality through encountering other persons. As a Lakota elder once remarked when asked, “Are all stone alive?” He answered, “No, but some are.”8 Those who are alive become animate to him when he enters into a direct relationship with them. In an interrelated world, everything is animate in relation to something else. Depending on the Indigenous culture, persons include animals, plants, lunar and solar phenomena, water, mountains, and in some cases, prayers, songs, glaciers, looms, and moccasins. In most traditions, persons share their power with others. Persons have inherent moral worth and are deserving of moral respect. The wording here is intentional. Moral worth is not an attribute of persons that can be separated from persons, and it is inherent in all beings.

Epistemology: Indigenous epistemologies are experiential, individual, empirical, practical, and flexible. Knowledge arises through interactions with other persons. It is personal, and relations with others create a shared knowledge community. Because knowledge is individual, Native peoples tend to be humble and avoid universal claims. Solutions for life’s problems drive knowledge acquisition and reflect the group’s interests, but their physical and theoretical environment limits the range of solutions available.9 The particular strategies employed or discarded depend on what works. If some acquired knowledge no longer has practical value, it can be discarded. Indigenous unified knowledge brings together theory and practice.

Ethics: For Indigenous people, the relational cosmos is moral, driven by life force. The main ethical principle is reciprocal responsibility.10 Persons have an obligation to respect the interests of others and find ways of interacting that promote mutual growth. Thus, the fundamental ethical problem relates to the need to survive, and survival requires food: “Who gets to eat whom, and under what circumstances?” If life force promotes growth, then the interests of the hunter and the hunted conflict. Neither’s interests outweigh the other’s. What matters is the survival of the group, not necessarily any individual. Often, moral covenants establish the proper etiquette and protocols required for maintaining appropriate relationships of respect.

Philosophy as a Moral Enterprise

From Indigenous perspectives, philosophy is a moral endeavor in three ways. First, it constructs a cognitive conception of the world. Second, as a unified approach to knowledge, it integrates all aspects of philosophy toward practical solutions. It places a moral responsibility on the philosopher to take Indigenous worldviews and lifeways seriously in a spirit of mutual respect and to broaden their own understandings of the world. To view their philosophies as curiosities and not take them seriously, the philosopher contributes to the difficulties Native peoples experience in their struggle to protect their sovereignty and land.

Final Comment

The essay attempts to open new avenues of thought among Western philosophers unfamiliar with Indigenous worldviews. The approach is to give a general overview. Space limits the detailed information necessary to provide specific applications of the theoretical notions described herein. But “one size does not fit all.” Navajo conceptions of reality are strikingly different from those of Tlingit, Lakota, or Iroquois. All, however, share aspects of the theoretical points developed above. All emphasize praxis. And all reflect a drive toward a unified theory of knowledge which integrates all aspects of philosophy. In sum, life force creates a relational cosmos through which persons come to know their world and act in ways that promote mutual care for others’ interests and well-being.

NOTES

1. Jefferey D. Anderson, “Space, Time and Unified Knowledge: Following the Path of Vine Deloria, Jr,” in Indigenous Philosophies and Critical Education, ed. George Dei (New York: Peter Lang, 2011), 95.

2. Anderson, “Space, Time and Unified Knowledge,” 101.

3. Gregory Cajete, Native Science: Natural Laws of Interdependence, foreword by Leroy Little Bear (Santa Fe, N.M.: Clear Light Publishers, 2000), 216.

4. For a detailed discussion of the moral nature of the cosmos, see Fritz Detwiler, “Moral Foundations of Tlingit Cosmology,” in The Handbook of Contemporary Animism, ed. Graham Harvey (Durham: Acumen Pub., 2013), 167–80.

5. Kenneth M. Morrison, “Animism and a Proposal for a Post-Carteian Anthropology,” in The Handbook of Contemporary Animism [Electronic Resource], in The Handbook of Contemporary Animism, ed. Graham Harvey (Durham, UK: Acumen, 2013), 49.

6. John Fulbright, “Hopi and Zuni Prayer-Sticks: Magic, Symbolic Texts, Barter, or Self-Sacrifice,” Religion 22, no. July 1992 (1992): 223.

7. Fritz Detwiler, “All My Relatives: Persons in Oglala Religion,” Religion 22, no. 3 (1992): 239.

8. Thomas M. Norton-Smith, The Dance of Person and Place: One Interpretation of American Indian Philosophy, SUNY Series in Living Indigenous Philosophies (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2010), 88.

9. Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, The Relative Native: Essays on Indigenous Conceptual Worlds, Special Collections in Ethnographic Theory (Chicago: Hau Books, 2015), 16–18.

10. Eva Marie Garroutte, Real Indians: Identity and the Survival of Native America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003), 118.