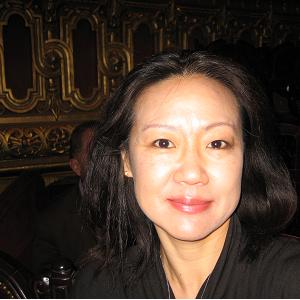

Jin Y. Park is Professor of Philosophy and Religion at American University. We invited her to answer the question “What does philosophy of religion offer to the modern university?” as part of our “Philosophers of Religion on Philosophy of Religion” series.

Jin Y. Park is Professor of Philosophy and Religion at American University. We invited her to answer the question “What does philosophy of religion offer to the modern university?” as part of our “Philosophers of Religion on Philosophy of Religion” series.

A rationalist approach to religion marked the beginning of the field of the philosophy of religion. Rene Descartes (1596–1650) claimed that it is the work of philosophers rather than theologians to prove the existence of God. Hegel (1770–1831) began lecturing on the philosophy of religion in 1821 and did so again in 1824, 1827, and 1831. He offered a grand scheme of the evolution of religions, assigning Asian religions to a primitive stage and Christianity to the culminating stage of that evolution. Regarding religious phenomena as “homogeneous,” he did not consider the possibility that different notions of the ultimate being or of humanity’s relationship to it are an expression, not of a religion’s relative primitiveness or maturity, but of different perspectives of the world and existence. This history of the philosophy of religion tells us what the study of the philosophy of religion can offer to the modern university.

Diversity and inclusion are a mantra of contemporary American universities. Frequently, though, this mantra fails to bring real change to college campuses, instead remaining as just rhetoric. By definition, the philosophy of religion investigates the act of religion. As I discussed in my earlier blog post “What is philosophy of religion?,” however, the widely accepted definitions of both “philosophy” and “religion” can be contested. In the East Asian traditions, these two terms might be understood in a very different way from how they are understood within the familiar Judeo-Christian religions. Hegel’s marginalization and depreciation of Asian religions clearly shows the limitations of the West-centered worldview. Likewise, studying the history of the philosophy of religion itself can help the modern university to challenge closed perspectives regarding diversity and inclusion by introducing different ways of viewing religions.

This leads to the second point that I would like to make. Modern society has been characterized as a secular one in which the meaning of religion and religious practice have gradually diminished. In his book A Secular Age, the Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor asked, “Why was it virtually impossible not to believe in God in, say, 1500 in our Western society, while in 2000 many of us find this not only easy, but even inescapable?” In the religious worldview, he tells us, “Human agents are embedded in society, society in the cosmos, and the cosmos incorporates the divine.” This holistic vision has gradually disintegrated in the modern world, as the standards for values have become secularized and individuals have developed a human-centered worldview as an alternative to the traditional theocentric world—the world in which the transcendental divine figure functions as a source of meaning and values in human life.

The religious world is a world in which people experience “a boundless awe” and “boundless wonders,” according to German theologian Rudolf Otto (1869–1937). In a secular age, however, the awe- and wonder-generating source of our existence is no longer an essential part of our meaning and value systems. This, however, does not mean that we humans are no longer looking for value and meaning in our existence. How do we resolve the conundrum of escaping the religion-centered world, but still keeping ourselves in the mode of constantly feeling boundless awe and looking for the source of our meaning-giving activities and values? I believe that the philosophy of religion offers this to modern universities and their students by reminding them of the values and meanings that used to play important roles in our lives.

The philosophy of religion is a mindful—not just rational—investigation of the act of religion. It reminds us that our modern busy lives constantly distract us from thinking about the real meaning and values of our existence, even if we’re constantly trying to define the fundamentals of being through the milieu of socializing and connecting with others through social media. It offers moments to dig up the aspirations that are buried in our hearts, forgotten because of the daily hustle and bustle of our routines.

In our time, the term “religion” frequently has a negative connotation, in part because it is now understood in the context of institutionalized religions in which the authority, conventions, and rituals mar, rather than encourage, religious practice. However, the drawbacks of institutionalized religion do not erase the need for religion in the human mind. In lieu of institutional religion, religiosity or spirituality should begin to represent the “content” of religious practice, freed from the power play performed by religious institutions.

Kim Iryŏp, a Korean Buddhist nun/thinker, repeatedly emphasized the importance of religious education and religious practice, which she considered as enabling us to realize the fundamental meaning of existence. For Iryŏp, religion did not constitute obedience to a creator God or transcendental figure’s moral commandments. The existential strain in her understanding of religion demanded a separation of religion from moral implications: “Religious education is not about making us do good things. It is about helping us recover the mind that knows how to erase the discriminating judgment of good and evil—that is, the original mind of human beings—so that we can live not by following fixed rules, but by relating to the contexts in which we find ourselves.” For Iryŏp, secular education helps in attaining knowledge, but religious education could lead an individual to “attain awakening.” Being awake meant having “established the foundation of your thought” and not being “manipulated by your circumstances. You form clear decisions about your projects and make consistent efforts to accomplish them.” Religion, for Iryŏp, was a way to discover the basis of human existence, and religious education was what enables us to be fully in charge of ourselves. We can replace Iryŏp’s term “religious education” with the philosophy of religion and then go back to the point that I made at the beginning of this essay regarding diversity and inclusion. Authoritarian morality divides us into a good people and bad ones instead of aiding us in understanding each other. The philosophy of religion helps us look deeper than the surficial differences and hierarchical moral judgments that accompany a superficial look at our lives, a feat that is truly needed in the modern university.