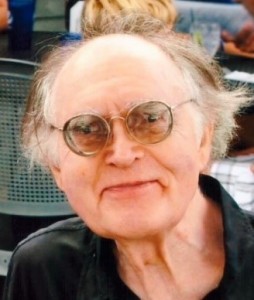

Rolf Ahlers is the Reynolds Professor of Philosophy and Religion at Russell Sage College. We invited him to answer the question “What does philosophy of religion offer to the modern university?” as part of our “Philosophers of Religion on Philosophy of Religion” series.

Rolf Ahlers is the Reynolds Professor of Philosophy and Religion at Russell Sage College. We invited him to answer the question “What does philosophy of religion offer to the modern university?” as part of our “Philosophers of Religion on Philosophy of Religion” series.

Philosophy of religion lives in the truth and guards skeptically against dogmatic decay of other sciences in the academy. What does that mean?

All thought is contextual. Thought’s objective context of reason is normative, necessary and unitary, while what thought thinks is contingent, for thought always determines what it knows. So we have three: the one context, the many determinants and mediating thought. That insight is basic to all knowing. Enlightening insight looks in and out: internal determination, e.g. self-determination, does not need external input. Similarly, empirical input from the outside also gains specificity and clarity through the modification it experiences in “being elevated into thought” in Hegel’s words. In both cases what is thought about is being changed in being determined. Philosophy of religion is and has always moved on those two planes: From antiquity to the present time we have known that God knows himself as self and other (Plato, Aristotle, John 1:1-5), and that knowledge is philosophy of religion. It has since the beginning claimed to be index sui et falsi, the criterion of itself as true and of what is false, similarly as light enlightens but also casts shadows. Since the very beginning real people like Plato, Plotinus, the Apostles John and Paul, people like you and I but also Pilate, Copernicus, Giordano Bruno, Darwin and Einstein have been part of that broad process of thought’s self-recognition in the history of thought and science, as also in political, economic and scientific history: in that history thought specifies itself as true, thereby also highlighting the false. The language and style of thought operative here has last gained prominence in Hegel; we claim here it has greater validity than for example what is known today as “structuralism”, “narrative philosophy”, “naturalism” and other similar oddities like “philosophy of gender and power studies”, “philosophy of mobbing” – the list of intellectual less rooted movements at modern universities goes on down to the idea that “ours is a post-metaphysical age”, the mother of all superficialities. What and how Darwin or Einstein thought cannot be separated from the ontology of thought thinking itself and what this implies theoretically. But empirical anthropology or sociology or economics or biology gained their potencies through a short-sighted rejection of the objective ontology of thought’s theoretical self-awareness. And that emancipation is, although empowering, reductive. No less reductive in the modern university is the universal acosmism, i.e. worldlessness of what is called “philosophy” or “religion” or other brainy disciplines such as “cybernetics”. Philosophy of religion recognizes and is skeptical of that acosmic reduction of the true heart of the university. The university is not only about providing tools for trade for lawyers or politicians or biochemists or teachers. The university is first and foremost about a disciplinary integrity that could only be achieved through an understanding how all thought coordinates truth and objectivity, and value and factuality, but that coordination is grounded in the distinction between truth and the lie. Distinguishing between truth as truth and the lie as lie gives greater weight to truth than to the lie. This is illustrated in Plato’s paradox of the lie: it is problematic to claim, as does the Cretan, as true that all positions including his own are lies. That means that some positions have more weight than others. The task is then to dislodge the half-truths and the lies in the academic world. Doing so is the skeptical side of philosophy of religion. It seeks to prevent decay into sociological description of religious practices or at the very least preserve a healthy discourse with value neutral sociology of religion, for such description has its place at the university. Also other natural sciences, e.g. Darwin’s insights, are no less central to philosophy of religion as are Einstein’s and that of all other scientists: after all, they are all part of the incredibly creative stream of knowledge’s self-realization in and through them. But there are forms of contemporary science from Marx’ “science of dialectical materialism” to Dawkin’s “science” that reject as “myth” or “delusional” Plato’s, the Bible’s, Spinoza’s and Hegel’s principle that truth is index sui et falsi. With that rejection “science” decays into dogmatism. And any dogmatism must be the object of skeptical critique by truth, for truth identifies the lie as a lie and so this identification points to the skeptical side of truth: Truth is skeptical of the lie and the half-truth. Our universities are populated with far too many dogmatists who claim the ideological mantle of “science” that has decayed to dogmatism. Philosophy of religion’s skeptical rejection of dogmatism throws a skeptical light on the dogmatism of confusing opinions with truth or to declare truth claims are ultimately not provable. Philosophy of religion is skeptical of the peaceful coexistence of all views and all sciences next to each other almost as if the rejection of any theodicy in the science criminology or in holocaust studies is indifferently coequal with Hegel’s philosophy of the spirit which is theodiceic in principle. That means: philosophy of religion would be skeptically watchful over curricular decisions as also over the very institutional structure of the university. In short: From Plato to Hegel skepticism was central for a philosophy worthy of that name. We claim such centrality of skepticism for philosophy of religion, modifying Luther’s pronouncement: Spiritus sanctus scepticus est: the Holy Spirit is a skeptic. The absence of such skepticism in the modern university has led to world-wide problems from the ecological crisis to economic and demographic and other imbalances on a global scale. To deal with such problems we would first need to recognize the problem in order to then build a real, modern university that overcomes dogmatic reductivism everywhere. That is as much a philosophical as it is a scientific or institutional responsibility: The task is as huge as it is necessary: The specialist in Heidegger needs to learn to talk meaningfully to theoretical physicists as well as to behaviorist economists.