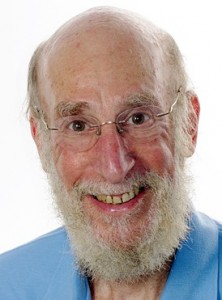

Douglas Allen is Professor of Philosophy at The University of Maine. We invited him to answer the question “What does philosophy of religion offer to the modern university?” as part of our “Philosophers of Religion on Philosophy of Religion” series.

Douglas Allen is Professor of Philosophy at The University of Maine. We invited him to answer the question “What does philosophy of religion offer to the modern university?” as part of our “Philosophers of Religion on Philosophy of Religion” series.

In answering the question of what the philosophy of religion offers to the modern university, it seems to me that one must engage in the difficult preliminary work of clarifying at least three key, confusing terms: the philosophy of religion, religion, and the modern university.

First, what is this “philosophy of religion” that may have something to offer the modern university? At an earlier time in what dominated the history of philosophy in the West, it seemed easier to define the traditional discipline and approach of philosophy of religion. Especially in the twentieth century, such dominant agreement and clarity have been shattered. Influential philosophers not only maintain that traditional proofs for the existence of God or solutions to the Problem of Evil are inadequate, but, more radically, that the traditional normative concerns of the philosophy of religion are based on linguistic confusion, category mistakes, and are meaningless. In my own work, I explore whether a more phenomenological approach in philosophy, in formulating the phenomenology of religion, could allow us to suspend those normative metaphysical and theological judgments and provide a more adequate basis for a philosophy of religion.

In addition, with greater exposure to and appreciation of the significance of the religious and spiritual phenomena of Asia, of indigenous peoples, and of other nonwestern cultures, one’s philosophy of religion increasingly expresses a recognition of pluralism and diversity, of hidden and camouflaged meanings, of complexity and contradiction. Therefore, it is a legitimate question as to whether there is even such a thing as “the philosophy of religion,” or whether we are examining complex, open-ended, diverse philosophies of religion.

Second, what is the subject matter, religion, of philosophy of religion? Once again, at an earlier time, it seemed easier to define religion in the dominant philosophy of religion in the West. Scholars typically assumed an essentialized concept of religion, usually formulated in Abrahamic, monotheistic terms of Judaism, usually Christianity (Judaeo-Christian usually versions of Christian), and occasionally Islam. Today, not only do we recognize that the terms religion and religions are much vaguer and more pluralistic and diverse, but we struggle with anti-essentialist and anti-universalizing challenges of relativism and of postmodernism, gender and ethnic and postcolonial studies, and other developments in recent decades.

Is there such a thing as “religion”? Does the philosophy of religion study religion as something that has defining characteristics, which allow us to distinguish religious from nonreligious phenomena and that have some objective and universal meaning? Or does the philosophy of religion study religion as a more dynamic, open-ended process of diverse subject matters without clearly defined structures and meanings?

Third, what is the modern university for which philosophy of religion may offer something? There was a post-Enlightenment view in the West that dominated conceptions of the modern university. The liberal arts and humanities, including my discipline of philosophy, were central to conceptions of the nature and function of the modern university. The study of religion at the modern nonreligious university was often regarded with suspicion, as if this were something premodern that lacked the rigor and objectivity of modern disciplines,

What is the situation today? As is well documented, the liberal arts and humanities, which usually include philosophy of religion, are increasingly under attack, underfunded, marginalized, with drastic cuts in faculty and programs, and often regarded as largely irrelevant to the modern university. That modern university is increasingly a corporatized university, which, using the post-Eisenhower conception of Senator Fulbright, is an integral part of the military-industrial-academic complex. Those with economic, political, and military power define the ends, and universities demonstrate that they can provide the means and are good investments.

Does this mean that the future of philosophy of religion in the modern corporatized university rests on convincing huge corporations that it can provide analyses of other religions and cultures necessary for penetrating and controlling foreign markets and maximizing profits from foreign investments? Does this mean that the future of philosophy of religion rests on convincing the C.I.A., the N.S.A., and others with political and military power that it can provide an understanding invaluable for dominant views of national security and the winning of wars? Or, as I believe, can a different view of the nature and function of philosophy of religion provide understanding that involves resistance to such developments in the modern university?

What we find today is multiple philosophies of religion or religious phenomena, highly diverse, situated, in need of contextualization, with both overlapping shared characteristics but also specific irreducible features. Some philosophers of religion in the modern university will do specialized research on specific religious perspectives. Others will bring multiple perspectives into complex dynamic relations, emphasizing encounter and dialogue and how our understanding of the other can serve as a catalyst for broadening and deepening our own understanding.

In assessing what philosophy of religion may offer the modern university, we can appreciate that the key terms of “philosophy of religion,” “religion,” and “modern university” resist closure and are open to creative contestation and development. The critical study of religion in the modern world remains important and exceedingly practical, as, for example, when we try to understand why the fastest growing religions seem to embrace a radical rejection of much of modernity and the modern university or why there is so much religious violence in the contemporary world. And philosophy of religion remains important and exceedingly practical for the modern university because philosophical reflection, on religious and other phenomena, is essential for critical examination and reasoning, for formulating general structures and relations, and for arriving at evaluations and judgments that are an integral part of any understanding.